Journal of HIV for Clinical and Scientific Research

Food Choices Made by Young Adults Living with HIV in a Unique Medically Tailored Grocery Program

1Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, USA

2Department of Nutrition, Boston University, USA

Author and article information

Cite this as

Smith KS, Rennick M. Food Choices Made by Young Adults Living with HIV in a Unique Medically Tailored Grocery Program. J HIV Clin Sci Res. 2025; 12(1): 009-015. Available from: 10.17352/jhcsr.000040

Copyright License

© 2025 Smith KS, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Introduction: A balanced, nutrient-dense diet improves quality of life in people living with HIV (PLHIV), yet this population experiences disproportionately high rates of food and nutrition insecurity. Food is Medicine (FIM) programs for PLHIV have been associated with reduced internalized stigma, improved food security, and positive clinical outcomes, but there is limited research on FIM interventions for adolescents and young adults with HIV.

Methods: The Medically Tailored Grocery (MTG) Program at Boston Children’s Hospital allows adolescents and young adults with LHIV who choose Instacart Fresh Funds to utilize a $200 monthly allowance within food category restrictions. We evaluated Fresh Funds participation from March 2024 to February 2025 and assessed fund usage, purchasing patterns, nutritional quality of purchased foods, and opportunities for nutrition education. Purchase reports were analyzed using Microsoft Excel.

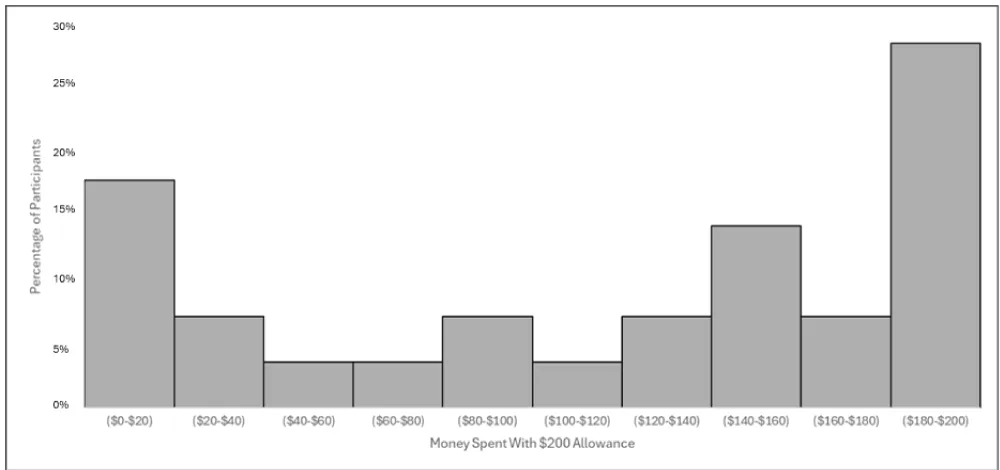

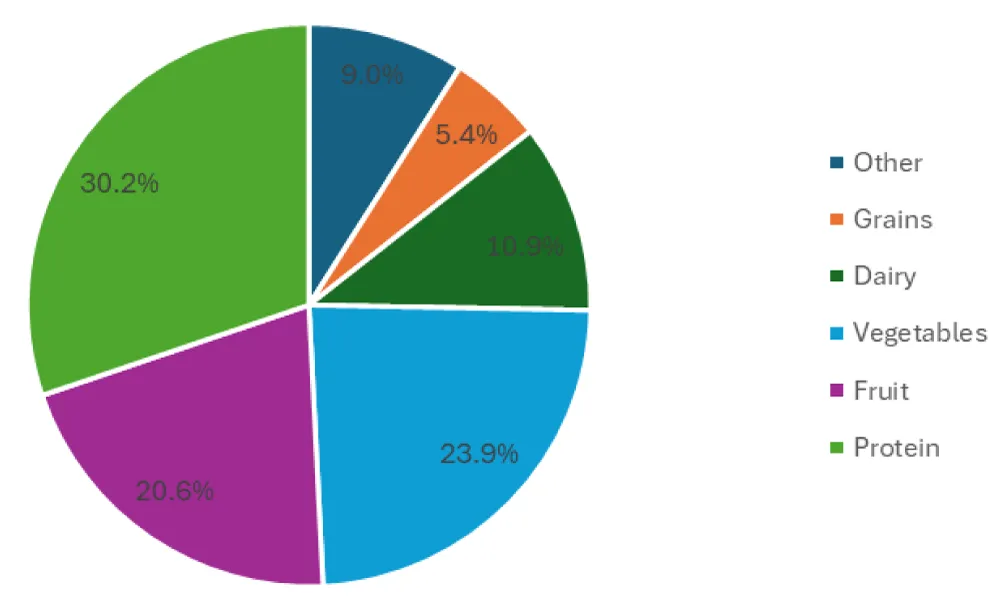

Results: Median monthly spending per participant was $141.64, with a bimodal distribution peaking at $0–$20 and $180–$200. Participants spent the highest percentage of their allotted funds on protein (29%), vegetables (23%), and fruit (20%), while grains accounted for the least amount spent (5%). Bread and yogurt were identified as important areas for nutrition education, as participants purchased the most products with added sugars in these categories.

Conclusion: While some participants consistently used their full allowance of Fresh Funds, a substantial portion underutilized the funds. Overalan MTG program providing healthy groceries for PLHIV allows them to shop on their own for pre-identified healthy foods, thus increasing their intake of nutritious foods, especially lean proteins, fruits, and vegetables.

HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus; PLHIV: People Living with HIV; FIM: Food Is Medicine; MTG: Medically Tailored Grocery; HAPPENS: HIV Adolescent Provider and Peer Education Network for Services; HRQoL: Health-Related quality of Life; ART: Anti-Retroviral Therapy; NAFLD: Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease; T2DM: Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus; FF: Fresh Funds; CC: Care Carts; BCH: Boston Children’s Hospital; STI: Sexually Transmitted Infection; CHAP: Children’s Hospital AIDS Program; IRB: Internal Review Board; HRSA: Health Resources and Services Administration; RD: Registered Dietitian; CI: Confidence Interval; NDMA: Non-Dairy Milk Alternatives; USDA: United States Department of Agriculture; BMI: Body Mass Index; MCHB: Maternal and Child Health Bureau; LEAH: Leadership Education in Adolescent Health; SNAP: Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC: Women, Infants, and Children

Introduction

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a communicable disease characterized by suppression of the immunnutrition further weakens immunity,people living with HIV (PLHIV) must have access to a balanced, nutrient-dense diet [1]. Specifically, a diet high in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, lean sources of protein, and unsaturated fats is recommended to avoid micronutrient deficiencies and maintain a healthy weight [2]. A 2023 cross-sectional study found that fruit and vegetable intake was positively associated with physical health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among 91 PLHIV [3].

Despite this, PLHIV face many disease-related barriers to adequate nutrition. Symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and mouth sores can reduce food intake, while HIV-related malabsorption may result in micronutrient deficiencies, including anemia [4]. Although historically HIV was associated with wasting, the widespread use of anti-retroviral therapy (ART) has shifted health outcomes to weight gain and lipodystrophy, increasing the risk of comorbidities such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [1].

PLHIV also experience socioeconomic barriers to accessing nutritious food. In 2022, 73% of PLHIV in Massachusetts were considered moderately high or highly socially vulnerable due to factors such as low income, minority status, and limited access to transportation [5]. As a result, food insecurity disproportionately affects PLHIV [6-8] and is associated with negative physical and mental health outcomes [9-11]. In a 2023 longitudinal cohort study of women HIV across the U.S., very low food security was associated with a 3.07 times higher relative risk of ART non-adherence compared to those with high food security [12]. Qualitative research suggests that this is because some medications taken on an empty stomach worsen side effects [11,13].

Several studies have addressed this issue through Food is Medicine (FIM) programs, which include nutrition education, nutrition supplements, medically tailored groceries (MTG), and/or food baskets [14-20]. Although outcomes vary, these programs have been associated with reduced internalized stigma [14], improved food security [15-17], and positive clinical outcomes such as improved hemoglobin, CD4 counts, and serum albumin [17-18]. However, there remains a significant gap in the literature regarding FIM programs for adolescents with LHIV.

The objective of the MTG program for PLHIV at Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH) was to increase nutrition variety and acceptability of healthy foods, improve confidence in healthy food preparation, and decrease food insecurity among young PLHIV by providing them with access to funds to use to purchase healthy foods, which could be delivered directly to their homes throughout the month.

The objectives of this study were to 1. Analyze the percentage of funds provided used by PLHIV and identify the food categories in which they were spent. 2. Evaluate purchasing patterns and food preferences of PLHIV when provided with Fresh Funds (FF) through Instacart. 3. Assess the nutritional quality of foods selected by PLHIV within the FF-eligible categories. And finally 4. Identify opportunities for nutrition education to assist PLHIV in making healthier choices within the RD-defined healthy food categories.

Materials and methods

Population

BCH HIV Adolescent Provider and Peer Education Network for Services (HAPPENS) is an HIV/STI prevention, screening, and treatment program for teens and young adults within the BCH Adolescent/Young Adult Medicine that also provfederally funded grantteensfederally funded grant HAPPENS is the recipient of a funded grant by Ryan White (HRSA) to provide healthy food delivery to support young PLHIV. In CHAPti on with the Childre,n’s Hospital AIDS Program (Cwithwith HIV ,with HIV these services were extended to additional patients not otherwise enrolled in HAPPENS. Approval for access to deidentified data from Instacart for this evaluation was obtained from the Boston Children’s Hospital Internal Review Board (IRB). Written informed consent was not obtained from participants, as the data provided by Instacart was completely deidentified with no registry.

Program description

Instacart is a digital food delivery platform that allows users to order groceries and other goods from various stores and have them delivered directly to the address of their choosing. Fresh Funds is a program within Instacart Health, a division of Instacart, which restricts allocated funds to be used only on products in categories specified by the program director. In our program, a Registered Dietitian (RD) was provided with a spreadsheet of food categories and was able to determine which sections were allowed in the HAPPENS FF program. Using the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) MyPlate and recommended healthy food intake as outlined by the USDA recommended daily allowances, the RD restricted the foods available in the FF program to: fruits, vegetables, lean protein, spices, healthy fats, and whole grains (Table 1). The categories were provided by Instacart and based on grocery categories and were not changeable. For example, whole-grain bread could be selected, but not whole-grain pasta because pasta is categorized by shape rather than ingredient. We could select yogurt, which is categorized by Greek and Icelandic or traditional, but could not specify whether to restrict to only unsweetened plain yogurt.

Intervention

For this program, 41 PLHIV between the ages of 12 and 32 enrolled in March of 2024 to either the Fresh Funds (FF) - where the participant was able to order groceries themselves from certain categories using their Instacart account - or Care Carts (CC) - where the groceries were ordered for them based on a food preference survey and were delivered to their house at the end of the month. This program, offered at BCH HAPPENS, used the online grocery shopping platform Instacart. It was provided as a supplemental healthy grocery program and not intended to provide a participant’s sole source of food for the month. Participants were able to apply for or utilize other sources of nutrition support, such as SNAP, WIC, or food pantries, if they qualified for those services. Originally, 29 chose FF and 12 chose CC. 6 participants switched from FF to CC due to not having a valid backup form of payment or inability to navigate the technology. Those who chose FF were given $200 per month to spend on FF-eligible items (Table 1), which were determined by an RD within provided categories dictated by the Instacart platform. The FF did not roll over and were renewed on the 1st of the month. They were not required to spend the monthly allocation fully, but if funds remained at the end of the month, the balance reset, and the remainder of the funds were no longer available to the participant. The program ended in February 2025. Nutrition education on making healthy food choices was not provided during the program, but participants were notified that this was a healthy grocery program with the understanding that the options made available to them were healthy choices. Further explanation of food options was provided on an individual, case-by-case basis to patients.

Analysis

We analyzed the full purchase reports, deidentified except for the month and year of purchase, provided by Instacart for the 23 consistent FF participants. We summed the total amount spent per food category across the program year and by month. We used monthly purchasing data to calculate the percentage of the FF monthly allowance spent per participant.

We also screened purchases to identify items that might contain added sugars or otherwise be of lower nutritional value (despite being allowed in the FF categories generally deemed healthy). We then searched for these items on Instacart to examine their ingredient lists and nutrition labels. Items deemed nutritionally suboptimal (sweetened yogurt, sweetened oatmeal, highly sweetened granola, refined bread or pasta, sweetened non-dairy milk, frozen mock meats, breaded or sweetened meat, excessively sweet or salty snacks, sweetened condiments and spreads, and sweetened fruits) were highlighted and color-coded for further analysis. Next, we calculated the proportion of Instacart categories containing highlighted items to identify areas for participant educational intervention or modification of Fresh Funds restrictions. All analyses were conducted through Microsoft Excel using the mean and 95% Confidence Interval (CI).

Results

Across the program period from March 2024 to February 2025, 23 participants spent $31,971.19 of their available Fresh Funds. Given a $200 allowance of Fresh Funds, the median monthly spending per participant was $141.64 (95% CI: $0.00, $199.60). The distribution of monthly Fresh Fund spending per participant was bimodal with peaks at the lowest ($0 - $20) and highest ($180 - $200) ranges (Figure 1). While a portion of the program participants took full advantage of their Fresh Funds allowance, another substantial group did not.

Category spending overview

Participants spent most of their Fresh Funds on protein, fruits, and vegetables, with grains accounting for the smallest share of spending (Figure 2). A detailed breakdown of spending by food category and subcategory is provided in Table 2.

Participants spent the largest share of their Fresh Funds on protein, fruits, and vegetables, categories which are generally health-promoting. Within the protein category, the most common purchases were lean animal proteins, including fresh or frozen poultry and seafood. This indicates participants largely prioritized healthier options over the few available red or processed meats. While some seafood purchases included processed items such as fish sticks and popcorn shrimp, these represented only a small share. Instead, the most frequent seafood purchases were salmon filets, canned tuna, and frozen shrimp. Spending on plant protein was notably lower, with legumes, nuts, seeds, and meat alternatives representing 11.5% of protein purchases. In the fruit and vegetable groups, participants were more likely to choose fresh produce over frozen or canned options .

Lower nutrient-density food choices

Non-dairy milk alternatives (NDMA) vary widely in nutritional content. Among participants who purchased NDMA, the majority selected lower-protein options: almond milk and oat milk accounted for 39% and 50% of purchases, respectively. In contrast, only 5% of purchases were soy milk, which is nutritionally comparable to cow’s milk in terms of protein content. Additionally, 19% of NDMA contained added sugars, including flavored varieties such as chocolate oat milk and vanilla almond milk, although most were fortified with Vitamin D and calcium.

Of the oatmeal purchased, 5,7% coadd,all granola contained added sugars. Rice cakes were a favorite snack, accounting for 19% of grain purchases. Significantly, 81% of these rice cakes were flavored, including “Caramel Corn Rice Cakes,” which contain 9g of added sugar per serving. Other notable purchases containing added sugars include condiments such as “Hot Honey”, “Chocolate Hummus,” and “Peanut Butter and Chocolate Spread,” however, these purchases were infrequent.

Instacart classification limitations

Instacart does not categorize yogurt by sugar content, so Fresh Funds users were able to purchase sweetened yogurts. Overall, 62% of the money spent on yogurt was spent on yogurts containing varying amounts of added sugars, up to 20g. Instacart categorizes yogurts into 4 groups: Greek and Icelandic, Traditional, Drinks, and Tubes and Pouches. Yogurt Tubes and Pouches, at 100%, had the greatest percentage of purchased yogurts containing added sugars, and Greek and Icelandic, at 63%, had the smallest percentage of purchased yogurts containing added sugars. With a total of $814.10 (66% of the money spent on yogurt), Greek and Icelandic yogurt was the most popular category of yogurt. Greek and Icelandic yogurts are typically higher in protein than other varieties and, as observed, were less likely to contain added sugars.

While Instacart allows more customization for bread restrictions, such as limiting selections to whole-grain varieties, refined breads are frequently misclassified as whole-grain products. For example, “Sweet Hawaiian Rolls” were categorized as Whole Wheat despite listing enriched wheat flour as the first ingredient and containing no whole wheat flour. Similarly, “Nature’s Own Multigrain Bread” was categorized as Whole Grain bread even though the primary ingredient is also enriched wheat flour. While it does contain sprouted wheat grains, whole oat groats, and sprouted rye grains, these contribute 2% or less of the bread ingredients by weight. In total, 63% of bread spending was on refined products despite being excluded from our selection criteria. Notably, 93% of Whole Wheat bread and 34% of Whole Grain bread purchwere actually refined. No participants chose to purchase from the Sprouted Grain category. Further investigation revealed that all Sprouted Grain bread available to purchase on Instacart met whole grain standards. These products, however, were considerably more expensive, ranging from $7.49 to $8.09, compared to the most frequently purchased bread, “Nature’s Own Honey Wheat,” which typically ranged between $3.65 and $4.99 depending on which store it was purchased from.

Discussion

Overall, spending patterns show that PLHIV participating in the HAPPENS FF Grocery Program prioritized protein, fruits, and vegetables over other categories of foods. This is a favorable outcom because these foods are often less accessible to those experiencing food and nutrition insecurity, due to shorter shelf life and higher cost [12]. Within the protein group, participants spent the most money on lean animal proteins, such as fresh and frozen poultry and seafood. Spending on plant proteins was lower, suggesting an opportunity for more education in this area. Grains accounted for the smallest spending. We hypothesize that participants may not prefer whole grains, leading them to use their FF on other categories. For example, rice, which is the most widely consumed grain globally [21], made up only 0.7% of grain spending. The only rice option they had available in FF was brown rice. This suggests that participants may be purchasing white rice outside of the program. Purchasing patterns within the dairy category, emphasizing almond and oat milk, also indicate nutrition illiteracy. These options are lower in protein compared to dairy milk. Yogurt purchases reflected similar complexities. While Greek and Icelandic yogurts, typically higher in protein and lower in added sugars, were the most popular, 62% of all yogurtspurchased contained added sugars. This highlights the limitations of the Instacart platform, which does not currently allow filtering by added sugar content, restricting participants’ ability to make fully informed decisions within program parameters.

More education is needed to provide patients with the tools that they need to make healthier choices when shopping for food, either on their own or using FF. This can be done during individual meetings with an RD or through educational handouts sent via text message or e-mail. Future programming may also require the limitation of certain categories where less healthful choices were repeatedly made if the Instacart platform continues to categorize foods broadly.

To the author’s knowledge, there are no other reviews examining the food choices made by PLHIV in an MTG program with which we can compare our findings.

The limitations of the study include the fact that our sample was small, may not be generalizable to all populations, and the results were not studied in conjunction with health outcomes. All patients who qualified were offered the prog; therenoocomparison population, and this was not a randomized clinical trial. However, this did demonstrate the use of a medically tailored grocery delivery program for young PLHIV and their food choices. Consumer feedback about the program and improvements in health parameters and clinical outcomes, such as cholesterol, BMI, and A1c, should be assessed in more detail with comparative analysis in the future.

Conclusion

This preliminary evaluation of our new program showed that PLHIV improved their intake during this FIM program, and helped decrease food and nutrition insecurity in similar ways to other FIM programs. Many participants would not otherwise have access to these foods, given the cost and shortened shelf life of fresh produce and proteins. When given choices, participants prioritized protein, fruits, and vegetables over other options such as whole grains, dairy, and spices. A medically tailored grocery delivery program for PLHIV can help to improve the eating patterns of PLHIV, thereby increasing their health status and decreasing health care costs.

Funding sources: Funding provided in part by a Ryan White HRSA grant for Ending the HIV Epidemic, and MCHB #T71MC00009 LEAH training grant.

Thank you to Elizabeth Woods, Susan Fitzgerald, Boston Public Health Commission.

- Willig A, Wright L, Galvin TA. Practice paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Nutrition intervention and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(3):486–98. Correction in: J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018;118(5):949. Available from: https://www.jandonline.org/article/S2212-2672(17)31816-9/fulltext

- Cheah JK. Nutrition requirements and nutrition intervention for people living with HIV/AIDS (Adults). JHAS. 2025;15:11–6. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0044-1787133

- Campbell LM, Montoya JL, Fazeli PL, Marquine MJ, Ellis RJ, Jeste DV, et al. Association between VACS index and health-related quality of life in persons with HIV: Moderating role of fruit and vegetable consumption. Int J Behav Med. 2023;30(3):356–65. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12529-022-10096-4

- Colecraft E. HIV/AIDS: nutritional implications and impact on human development. Proc Nutr Soc. 2008;67(1):109–13. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/proceedings-of-the-nutrition-society/article/abs/hivaids-nutritional-implications-and-impact-on-human-development/2DE7DF2C0B7E943E6DD8044A7AF38D61

- Massachusetts Department of Public Health, Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Sciences. Massachusetts HIV epidemiologic profile, statewide report – Data as of 1/1/2024. Boston (MA): Massachusetts Department of Public Health; 2024 Jun. Accessed 2025 Apr. Available from: https://www.mass.gov/lists/hivaids-epidemiologic-profiles

- Raja A, Heeren TC, Walley AY, Winter MR, Mesic A, Saitz R. Food insecurity and substance use in people with HIV infection and substance use disorder. Subst Abus. 2022;43(1):104–12. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/08897077.2020.1748164

- Spinelli MA, Frongillo EA, Sheira LA, Palar K, Tien PC, Wilson T, et al. Food insecurity is associated with poor HIV outcomes among women in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(12):3473–7. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10461-017-1968-2

- Bleasdale J, Liu Y, Leone LA, Morse GD, Przybyla SM. The impact of food insecurity on receipt of care, retention in care, and viral suppression among people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States: a causal mediation analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1133328. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1133328/full

- Palermo T, Rawat R, Weiser SD, Kadiyala S. Food access and diet quality are associated with quality of life outcomes among HIV-infected individuals in Uganda. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62353. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0062353

- Wang EA, McGinnis KA, Fiellin DA, Goulet JL, Bryant K, Gibert CL, et al. Food insecurity is associated with poor virologic response among HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral medications. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(9):1012–8. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11606-011-1723-8

- Whittle HJ, Palar K, Seligman HK, Napoles T, Frongillo EA, Weiser SD. How food insecurity contributes to poor HIV health outcomes: Qualitative evidence from the San Francisco Bay Area. Soc Sci Med. 2016;170:228–36. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953616304372

- Palar K, Sheira LA, Frongillo EA, Kushel M, Wilson TE, Conroy AA, et al. Longitudinal relationship between food insecurity, engagement in care, and ART adherence among US women living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2023;27(10):3345–55. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10461-023-04053-9

- Musumari PM, Feldman MD, Techasrivichien T, Wouters E, Ono-Kihara M, Kihara M. "If I have nothing to eat, I get angry and push the bottle away from me": A qualitative study of patient determinants of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in the Democratic Republic of Congo. AIDS Care. 2013;25(10):1271–7. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09540121.2013.764391

- Maluccio JA, Wu F, Rokon RB, Rawat R, Kadiyala S. Assessing the impact of food assistance on stigma among people living with HIV in Uganda using the HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument-PLWA (HASI-P). AIDS Behav. 2017;21(3):766–82. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10461-016-1476-9

- Fahey CA, Njau PF, Dow WH, Kapologwe NA, McCoy SI. Effects of short-term cash and food incentives on food insecurity and nutrition among HIV-infected adults in Tanzania. AIDS. 2019;33(3):515–24. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/aidsonline/Fulltext/2019/02150/Effects_of_short_term_cash_and_food_incentives_on.17.aspx

- Palar K, Sheira LA, Frongillo EA, O'Donnell AA, Nápoles TM, Ryle M, et al. Food is medicine for HIV: Improved health and hospitalizations in the Changing Health through Food Support (CHEFS-HIV) pragmatic randomized trial. J Infect Dis. Published online 2024 May 2. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/advance-article/doi/10.1093/infdis/jiae195/7649484

- Benzekri NA, Sambou JF, Tamba IT, Diatta JP, Sall I, Cisse O, et al. Nutrition support for HIV-TB co-infected adults in Senegal, West Africa: A randomized pilot implementation study. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):e0219118. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0219118

- Nyamathi AM, Shin SS, Sinha S, Carpenter CL, Garfin DR, Ramakrishnan P, et al. Sustained effect of a community-based behavioral and nutrition intervention on HIV-related outcomes among women living with HIV in rural India: A quasi-experimental trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;81(4):429–38. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jaids/Fulltext/2019/08010/Sustained_Effect_of_a_Community_based_Behavioral.6.aspx

- Reid C, Courtney M. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate the effect of diet on weight loss and coping of people living with HIV and lipodystrophy. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(7B):197–206. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.01915.x

- Martinez H, Palar K, Linnemayr S, Smith A, Derose KP, Ramírez B, et al. Tailored nutrition education and food assistance improve adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: Evidence from Honduras. AIDS Behav. 2014;18 Suppl 5(0 5):S566–77. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10461-014-0786-z

- Poutanen KS, Kårlund AO, Gómez-Gallego C, Johansson DP, Scheers NM, Marklinder IM, et al. Grains – a major source of sustainable protein for health. Nutr Rev. 2022;80(6):1648–63. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/nutritionreviews/article/80/6/1648/6312055

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley